Book Review: Andrew Phillip Smith The Lost Teachings of the Cathars, Watkins Books 2015

It’s easy to get overwhelmed when trying to get your head around a religious movement. The moment we get beyond catchphrases and pop culture references, the ideas and experiences that lay behind words like “Tantra” or “Gnosticism” can quickly result in the need to have a bit of a lie down in a darkened room.

Given the potential complexity of such terrain, it always comes as a relief when you find an author who is able to maintain the precarious balance between factual accuracy, readability and contemporary relevance. In the realm of Gnostic studies Andrew Phillip Smith has consistently been such a voice. Not only has he been editor of the fabulous journal The Gnostic but he has also penned a clutch of super-helpful volumes such as The Secret History of the Gnostics and A Dictionary of Gnosticism. In The Lost Teachings of the Cathars, Andrew has now turned his attention specifically to the issue of how the Gnostic religious impulse has continued from antiquity into the medieval period and beyond.

The first part of the book provides us with a well-written account of the Cathars as a religious movement, and their likely connection to other groups such as the Paulicians and Bogomils that pre-dated them. While there are a number of other books out there that cover similar territory, Smith’s account reads like a lively travel journal that incorporates both his own travels through regions such as the Languedoc, and his insights regarding what we know about Cathar teachings and their connection to earlier forms of Gnosticism.

While the Cathars can rightly be viewed as exemplifying a heroic attempt at religious freethinking, their story is ultimately a tragedy. The period between the 11th and 14th centuries in which they flourished in southern France and northern Italy was continually beset with conflicts with the orthodox Roman church, which they viewed as corrupt and in thrall to a false understanding of both God and salvation. Although there was variety and complexity in what we know of Cathar belief, it is generally agreed that they were dualists who viewed the realm of matter as being the product of a lesser god.

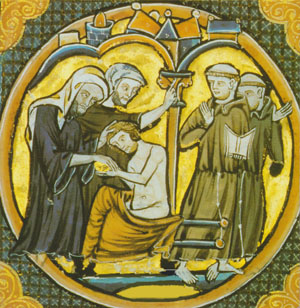

What Andrew’s book does more fully than most studies of Catharism is to closely consider their practices and their likely significance within the community of believers. He explores the available material that we have regarding their primary sacraments such as the consolateum and the apparellamentum, as well as the purpose behind the celibacy and vegetarianism adopted by the group’s adepts (the Perfecti). He also examines the manner in which their radical reinterpretation of Christ’s teaching ultimately brought them into such violent conflict with both civil and ecclesiastical authorities. Whatever one makes of their dualist theology, it is hard to remain unmoved by the devastating holocaust that was inflicted upon them at Montsegur at the culmination of the Albigensian crusade.

Brother on Brother Action

Most of the previous books that I have read on the Cathars have tended to end here, trying to make sense of these peace-loving mystics who fell foul of a corrupt church so desperate to hold on to its ability to control. Here though, what Smith does next is consider the way in which the last embers of the Cathar tradition have been revived by various teachers and groups in subsequent centuries. Like so many traditions that produced few written documents to define their teachings, the Cathars have become a screen onto which all manner of groups and writers can project their own desires and agendas.

From here it gets both weird and interesting as we get to dig into some more recent history. Otto Rahn’s imagining of the Cathars as the custodians of the Grail brought him to the attention of Himmler and the SS (Indiana Jones anyone?) and probably contributed to his early demise. Also we have the French Gnostic Church getting revived (in 1889) via disembodied Cathar Bishops turning up at séances, and perhaps most spectacularly we have a mass Cathar reincarnation occurring in Bath, England. This latter story of an English psychiatrist being convinced by a patient that both of them were reincarnated Cathars, illustrates something of the way in which they have become a conduit via which the aspirations of our Aquarian age have been funnelled.

While lesser authors (and cynical chaos magicians) might take cheap shots at the nature of these explorations, Smith examines such efforts in a spirit that is at once critical and yet generous in understanding them as part of our shared human attempts to find meaning and identity. Such generosity is to be applauded and to my mind reflects a tolerance that the Cathars themselves would have welcomed.

Highly recommended.

For a chance to see Andrew and myself co-presenting about the Gnostics at the Occult Conference in Glastonbury, here’s a link! http://www.occultconference.co.uk/schedule/speakers/exploring-gnosticism

SD