It’s probably not very surprising that I find myself trying to write a reflection on how Queerness and Gnosis intersect given the importance they both play in my life. My blog posts, and the book A Gnostic’s Progress, bear witness to my attempt to explore the complexity of human life and how we utilize experiences of direct knowing in our attempts to manage the dilemma of existence.

While others may view the conflating of Queer experience and Gnosticism as being a personal eccentricity or indulgence on my part, I would ask for your patience as I try to unpack some of the resonances that I experience. For me the starting point for both the Queer-identified and the Gnostic is a sense of discomfort and dislocation in response to binary attempts at classification.

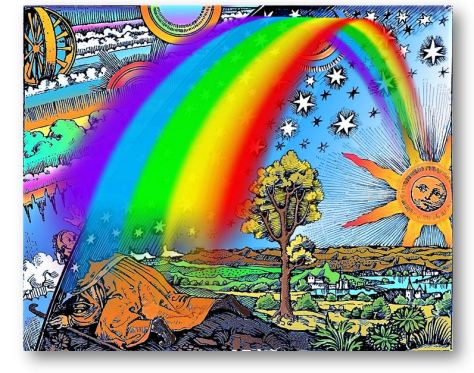

While the Gnostics are often typified as dualists, for me a large part of what lies at the heart of gnostic exploration is dissatisfaction with attempts to divide our experience of the world along binary lines. An orthodoxy that seeks to classify things in terms of the works of God or those of Satan made little sense to those religious free-thinkers who wanted to embrace complexity more fully. Rather than being satisfied with the simple answers of faith, the Gnostic sets out into deep space in order to explore the tension, complexity and contradiction that seems to lie at the heart of life’s mystery.

The Gnostic is the sacred scientist in the truest sense in their attempts to openly explore; question and pressure test their findings. Their metaphysical insights may fail to meet the rigour of the strict reductionist, but their attempt to map the weird cosmologies experienced through inner perception still provide us with much of value. These strange inner landscapes had a clear resonance with depth psychologists such as Carl Jung as he felt that they provided insight into the nature of human experience and how we might work with the process of personal transformation.

Early Gnostic cosmologies such as those mapped out by early groups, for instance the Sethians and Valentinians, contain a wide variety of spiritual couplings (or syzygies) that seek to convey the dynamic dance at work in the process of creation. For the Gnostic, the numinous realm is full of a wide array of beings such as Aeons, Archons, Powers and Principalities, all vying for expression and manifestation into both matter and the realm of human consciousness. While diagrammatic attempts to depict such systems usually come off looking quite linear, in reading the oft-confusing description of them in primary Gnostic texts, the heavenly host often feels far more fluid, over-lapping and multi-directional.

For me the Gnostics embody a type of heretical free-thinking that seeks to challenge a form of certainty that relies on blinkered tunnel-vision. Neat delineations that require us to ignore the messy complexity of our deepest longings are challenged by the heretics’ brave act of choosing. While the pedlars of certainty proclaim loudly that their polarised, black and white world is either the result of natural order or God’s will, the heretic is listening to a quieter inner voice.

The awakening to Queerness can of course happen in a whole host of ways. It might be an internal awareness of the complexity of desire or (as was in my case) communication from the straight world of the demi-urge that my way of presenting was not working for them! These realisations may happen suddenly or in a more slow-burn fashion in which you become increasingly aware of dissonance. Whichever speed it happens at this is a profound unfolding of who we sense we are and for me it definitely had a Gnostic dimension. If the admonition to “Know Thyself” was to have an authenticity then it needed to account from the outsider experience that I experienced as a Queer person.

Gnostic explorers of most stripes are usually willing to question what we mean by the natural. In trying to grapple with the discomfort associated with our experience of living, they sought to question the narratives about this transmitted by both Church and State. These organs of authority have been keen to get us to believe all sorts of ideas, in the name of their being natural. Whether it’s the inevitability of reproduction, the subjugation of Women or the exclusion of Black people, both Church and State have the potential to become archonic in their restriction of personal expression and liberty. In their attempt to control and contain they seek to minimise the complexity of our life experience and to present a dominant narrative that limits the possibility of a deeper connection based on a truly rich diversity.

The syzygies so loved by the Gnostics often sought to embody a richer story in which the binaries experienced were held together as they moved through a process of reconciliation. Manifestations of this unification often pop-up in androgynous figures such as Adam Kadmon or Abraxas, but I think that we risk losing something crucial if we see them as fixed icons and fail to appreciate the Queer dynamism that they embody. Queerness often presents a disruptive challenge to our attempts at neatness. At best it moves beyond mere hip theorising and compels us to enact, perform and intensify the often blurry reality of who we are.

In this fluid dance, Queerness can be experienced as identity, mood and the dynamic that exists in the interactions between people, objects and organisation. For me it provides a way of knowing that provides not only a space for inhabiting the present, but also a lens for viewing the past. In asking us to stay awake to sensitivity to context and process, Queerness provides a necessary challenge to the type of brittleness that can come when we get overly invested in fixed identities. In my view, such a dynamic creates a type of optimism as I see glimpses of the type of human creativity that Jose Esteban Munoz refers to as “Futurity”.

I have already spoke of the inspiration that I have gained via Nema’s description of N’Aton as an embodiment of our future magical selves, and part of my attraction to this figure is in the way it manifests a type of magical optimism and Futurity. Depictions of N’Aton often hold together the individual and collective perspectives and for me such images embody a type of spiritual awakening that allows for a multiplicity of perspective. When we step away from the tunnel-vision of either Christian or Orthodox Thelemic eschatology, we can begin to explore the Queer possibility of our aeonic utopias overlapping, blurring with and potentially strengthening each other as they balance and inform each other’s insights.

This is a tightrope walk in which we try to balance the reality of both our individual and collective struggles with the need to explore the possibility of what hope might mean. When the Archons shout their “truth” so loudly, we must dare to keep the richness of our stories alive! I’ll end with this great quote from Sara Ahmed in which they discuss the possibility of what we might create when we radically reappraise the type of future we might have:

To learn about possibility involves a certain estrangement from the present. Other things can happen when the familiar recedes. This is why affect aliens can be creative: not only do we want the wrong things, not only do we embrace possibilities that we have been asked to give up, but we create life worlds around these wants. When we are estranged from happiness, things happen. Happiness happens.

The Promise of Happiness p.218

SD