Having spent some recent posts thinking about Queer theory and how it can shape aspects of magical practice, I thought it might be worthwhile considering the way in which Queerness impacts on the way we may choose to read and use history in finding inspiration for our spiritual journeys. I have always been a bit of a history geek and was in a definite minority as a theology undergraduate in wanting to dig into the way in which personality and politics intersected in the human attempt to find religious meaning. While others may have viewed the early Gnostics or the pre-Whitby Celtic Church as dull, I dug deep into these ecclesiastical detective stories as they provided such a rich means for understanding the questions that I was personally engaged with.

The reading of any text is a complex process in which the information provided is inevitably shaped by the world view of the reader. This awareness of how our own perspectives or “presupposition pool” influences our interpretation is central to the field of hermeneutics. While hermeneutics originally developed in relation to the understanding of biblical and other sacred texts, its insights were eventually adopted in a broad range of human sciences, and its philosophical implications were explored by philosophical figures as august as Heidegger and Hans Georg Gadamer. We are all engaged in hermeneutics, and our own biases and contexts inevitably shape the pair of glasses or ‘lens’ through which we seek to make sense of something. What hermeneutics has been hugely helpful in making historians more aware of, are the dangers that our readings might face if we are less conscious of how our own biases and contexts impact on our explorations.

In my recent explorations of Gnosticism, and religious freethinking more generally, I have been increasingly aware of my own lens as a person who identifies with many aspects of Queer identity. When one is trying to comprehend how a person’s Queerness might shape their process of interpretation we have to acknowledge that we are already contending with a highly fluid concept that defines itself by its ability to defy easy categorisation. That being said, the experience that I have as a reader of religious history is one in which my own experience as a sexual and gender outsider sensitises me to similar themes that I empathically sense within the narratives with which I am engaging.

Now this all sounds very heady, so it might be helpful to provide an example of how something has recently inspired me and how my context has shaped the themes that have emerged for me.

Beguines and Beghards

Not nuns

I’ll start by stating that the spiritual movement of the Beguines—and their male counterparts the Beghards—is impossible to summarise succinctly given the diversity of their geographical contexts and the historical time span during which their movement was most vibrant. For more information check out the wiki entry, and books such as Beguine Spirituality by Fiona Bowie, and the more recent The Wisdom of the Beguines by Laura Swan.

In summary, the Beguines were a network of predominantly female lay communities that sought to pursue their own sense of vocation outside of formal monastic rules and orders. The golden age of the Beguines was between the 12th and 16th centuries, and their communal houses (Beguinages) thrived most readily in the Low Countries of Europe i.e. the area including Belgium, the Netherlands, and bordering on France and Germany.

While the Beguines were devoted to the monastic ideals of celibacy and simple living, each house was free to evolve its own rule, and these communities were noted for their continued involvement in commerce (especially the textile trade) as a means of supporting themselves. They were noted mystics who placed a high value on visionary experience, and some scholars have noted the influence of the troubadour and courtly love traditions in relation to their passionate longing for union with the beloved.

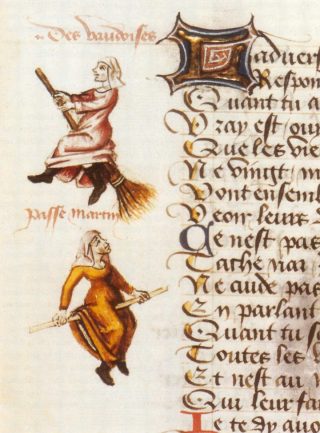

As with so many radical and visionary groups in the medieval period, the Beguines aroused a decidedly mixed response from those in authority. While they were initially seen as embodying a high level of piety, the rate at which women joined the communities was often seen as a threat to male power and control. The Beguines had not submitted a common rule for Papal approval and their emphasis on mystical experience almost inevitably drew accusations of heresy. They received Papal condemnation in 1311 and in the previous year, one of their most outspoken leaders Marguerite Porete was burnt at the stake for failing to renounce her visionary work The Mirror of Simple Souls. Despite their devout lives, church authorities often saw connections between the Beguines and more overtly antinomian groups, such as the Brethren of the Free Spirit.

In subsequent centuries the Beguines underwent several waves of renewal and rehabilitation, but the Reformation, and the decline of the textile trade (their main source of income), eventually contributed to their numbers diminishing. While the anti-monastic agenda of the Reformation inevitably impacted on the Beguines, their continued involvement in health care and education provided them with an important social function; Beguine communities continued in Belgium until the early part of the 20th century.

Queer Readings

My Queer reading of this history occurs at a number of levels and undoubtedly has considerable intersects with both Feminist and Anarchist readings of Beguine history. While my own lack of Christian faith may inevitably create some metaphysical distance between my and their spiritual experience there is still much that I connect with. Here are a few banner headlines:

- Organisational liberty. The Beguines inspire me in their determined rejection of centralised authority. While they situate themselves firmly within the pre-Reformation Catholic faith, their desire to shape their own paths at a local and communal level has many connections to the way Queer activism challenges us to pursue social change.

- Personal gnosis. While the religious language of their society was still core to Beguine experience, in the face of male dominance in the Priesthood and other Ecclesiastical domains they found power and self-definition through visionary experience. Similarly, Queer identity—while using the language of culture regarding orientation and gender—retains the right of the individual to blur and play with these concepts in order to locate a ‘best-fit’ version of self.

- Rejection of heteronormativity and an increase in Female Power. The Beguines freaked the church out. These women found a collective means for self-definition and a rejection of potentially endless, life-threatening reproduction. Themes around an increase of female power were also vital to Gnostic groups such as the Cathars during the same period, and the threat that both groups posed to male dominance was a likely catalyst to the later witch trials of the Early Modern period.

Beginning to do it for themselves

Such reflections are far from definitive and are presented as serving suggestions as to how Queer (or other) lenses might be employed. The conscious use of such approaches can be hugely inspiring, and my own engagement with groups such as the Beguines are part of my own personal explorations of themes as diverse as New Monasticism and the impact of Christian heresy on Witchcraft traditions. The viewing of old history with a fresh set of eyes can often provide us with rich veins of new material.

SD