Reading is good. Reading does all sorts of great stuff to us, it provides stimulus, transports us to new worlds and at best promotes curiosity. In my last post I had the pleasure of reviewing Andrew Phillip Smith’s excellent The Lost Teachings of the Cathars and like many a good book it left me with as many questions as it provided answers.

The Cathars have always proved to be something of an enigma. While on one level they provide a vivid example of how Gnostic religion survived into the medieval period, it can still be problematic trying to discern what they did and did not believe. This is partly due to history often belonging to the most powerful, i.e. the Church and the Inquisition, but it may also reflect a religious tradition more focused on a living encounter with mystery, rather than codifying a systematic theology.

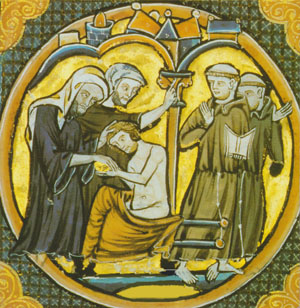

Cathar cross

What does seem clear about them, is that they were incredibly courageous in being willing to question the orthodoxies that the Church and State were hugely invested in maintaining. As with the Gnostics of antiquity, Cathar theology seems to have been derived from an encounter with a God who seemed irreconcilable with the material realm. The stark realities of human pain and impermanence led to them adopting a worldview that was a radical inversion of Church teaching.

The Cathars’ dualism meant a rejection of the creator God. By extension they rejected the Church teaching that the project of marriage and reproduction was actually a good idea. If your view is that the material realm needs to be escaped from, then the entrapment of even more spiritual beings tends to not be viewed positively. Not only were the Cathar Perfecti clear in their rejection of sexual activity that could lead to childbirth, they viewed marriage itself as negative and were accused by the church as advocating abortion.

The historic connection between the Cathars and the Bulgarian Bogomils is fairly well attested, and the accusation of the latter engaging in “buggery” and other forms of non-reproductive sexual activity may have some credence beyond mere slander. The terms Bogomil originally meant “Friend of God”, but those threatened by their Gnostic teachings were so persistent in their accusations of sodomy, that the group became synonymous with anal activity. It may well be difficult to ascertain whether the Perfecti themselves were absolute celibates, but it seems probable that an engagement in non-penis in vagina sex in the wider Cathar church was consistent with their desire to avoid pregnancy.

Whatever one makes of their dualism, it’s fascinating to consider how these themes of inversion and the unnatural became central to not only the persecution of heretical groups such as the Beginues, Cathars and the Brethren of the Free Spirit, but also how such themes contributed to the perception of Medieval Witchcraft. As Norman Cohn has rightly highlighted, the accusations brought against the alleged practitioners of Witchcraft are as old as time its self. Accusations of sexual depravity, cannibalism and abortion are the stock-in-trade for those in power wanting to depict a religious minority as being the hidden cause of societal unrest. Jews, Christians, Gnostics and practitioners of Magic have all been persecuted on the basis that they engaged in such activities and that their practice of such unnatural inversions is a direct threat to the well being of the masses. Such acts of depravity either promoted the presence of disorder and disease e.g. the Black Death, or they invited divine retribution due to the failure to eradicate such miscreants.

What seems fairly clear is the manner in which minority groups such the Cathars and those accused of Witchcraft became a location onto which the fantasies and fears of those in power could projected. Whether it was the imagined orgies of Witches at the Sabbat or Cathars having tonnes of Queer sex, their status as outsiders, without real power and recourse to stable judicial process, made them highly vulnerable to persecution. Sadly, history confirms that such strategies of distancing and demonising only make it easier for the powerful to view such minority communities as dangerous, threatening and therefore disposable and warranting of savagery.

In light of the recent traumas inflicted by both the UK’s Brexit vote and the US presidential elections this can seem like decidedly bleak reading. Indeed those of us seeking to avoid such catastrophes must know, understand and promote awareness concerning such saddening examples of powers’ misuse. But dear friends, be of stout heart! These heretic heroes provide us with some keys for reclaiming both power and the magics of conscious subversion.

Never again the burning times

While some occultists may sneer at the way that the Witch as truth-teller has been co-opted by the so-called “liberal agenda” (like that’s such a bad thing?) recent events in Poland provide us with a powerful example of liberation. In being faced with a parliament hell-bent on implementing draconian laws aimed at further restricting Women’s access to safe and legal abortions; the Witches took to the streets. Thousands of black-clad (predominantly women) activists downed tools and protested as a potent and defiant “fuck you” to those who sought to further their control. While the battle for religious and reproductive liberty is ongoing, I couldn’t help but smile and be inspired at a social media post by a Polish friend of mine who had taken part:

“We are the granddaughters of all the Witches you were never able to burn.”

For most of us, the pursuit of spiritual paths that involve magic and gnosis entails a direct challenge to the forms of reality that the mainstream wants us to accept. We are the inverts, the Queer and the outsiders seeking to push forward the liminal edge of our cultures, so that they may evolve and that we may have space to thrive. I do not reject nature and the wild beauty of our world, but I continue to question concepts of what it means to be “natural” within it. Concepts of fixity and desires for a romantic stone age should be open to questioning and as a heretical freethinker I will continue to do so.

Hail to those seeking liberty, diversity, kindness and freedom! May we be inspired to new levels of wisdom and action, by those heretical heroes who have come before us.

SD