Hello Friends,

Here in the northern hemisphere the equinoctial shift has passed and we begin to enter the rich darkness. The new academic year begins and we move inside, away from the frolics of the summer, and our attention is once more drawn within. As they say in psychedelic therapy ‘the darkness is where the treasure lies’; the darkness may be challenging but it is also in this deep within that insights can be found.

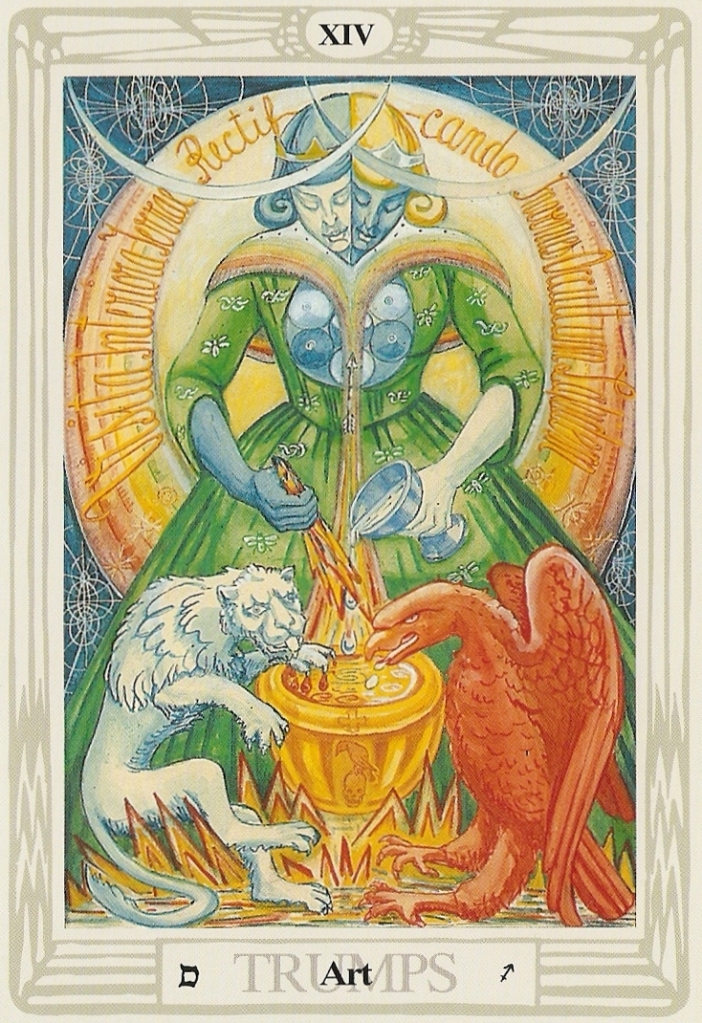

Like it says on the Thoth Tarot card Art (aka Temperance): “Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapiiderm”, Latin for “Visit the interior parts of the earth; by rectification thou shalt find the hidden stone.” The hidden stone is the philosopher’s stone. Rectification is an alchemical process of purification through repeated distillation. In the dark part of the year we distil and refine what we have learnt in the bright months to create the conditions for transformation.

I hope that you’ve been able to grow successfully this year and if, like me, you are feeling that northern descent into the darkness, you can experience it as nourishing, empowering and good.

I’m very pleased to have been invited to do more psychedelic teaching this year on Laura-Dawn’s Transilience Program and for the Stewards of the Sacred Global Online Gathering led by Natasja Pelgrom (details to be released soon).

I’m also offering a workshop on Psychedelic Magic with Treadwell’s and looking forward to working with the fabulous Fungi Academy at their HQ in Guatemala teaching on the Sacred Space Holder Program.

This autumn also sees me showing some of my magical art at St Ives in Cornwall from the 4th to the 9th of November alongside Kate Southworth and Greg Humphries. Collectively we’re known as The Order of the Sun and Moon, a name taken from the title of an essay by artist-occultist Ithell Colquhoun.

We’re running a series of both online and live events including discussions, rituals and workshops. You’re also invited to attend the private view of the gallery, just drop me a message to contactdeepmagic@gmail.com to let us know you’re coming along.

I’d also like to draw your attention to the work of The Good Beast with their swirling psychedelic sound and cool merchandise that features an artwork by me 😀 Their first album is launched this month.

And just for fun I’ll be visiting Berlin for a second time this year to attend the Occulture Conference. I’m not to speak this time so I can focus on the delight of simply hanging out at Europe’s foremost occult conference.

Closer to home, my old home city of Bristol in fact, I’m doing a talk about Psychedelic Magic at the local Pagan moot. Here’s the fabulous poster that a friend designed for the event:

Finally, I’m doing a deep dive into the Thoth Tarot online in November, suitable both for complete novices to the tarot and to old hands with the Thoth or other decks.

Sending you best wishes, dear friends, for your autumnal adventures – or spring explorations for those in the southern hemisphere – and hope I’ll see you online or in person soon.

Much love from sunny Devon!

Julian